On a cold winter day in February, my husband and I finished lunch at one of our favorite spots. We’d missed dining there since we moved away, so we combined some errands and finished the morning slurping noodle soup, perfect for a mid-winter day.

“We really should check on Harry,” I said to my husband as we finished up. “Maybe he can’t hear the phone anymore.” “Or, maybe he never fixed the doorbell,” replied my husband. We had not been able to connect with Harry for about a year. We called every so often and had gotten no answer. I had met his daughter once under tragic circumstances and couldn’t remember her married name.

This is a story about how someone can become so isolated that no one cares if anyone else knows what happened to him. It’s also a story of how people hide information that is simply too painful to talk about.

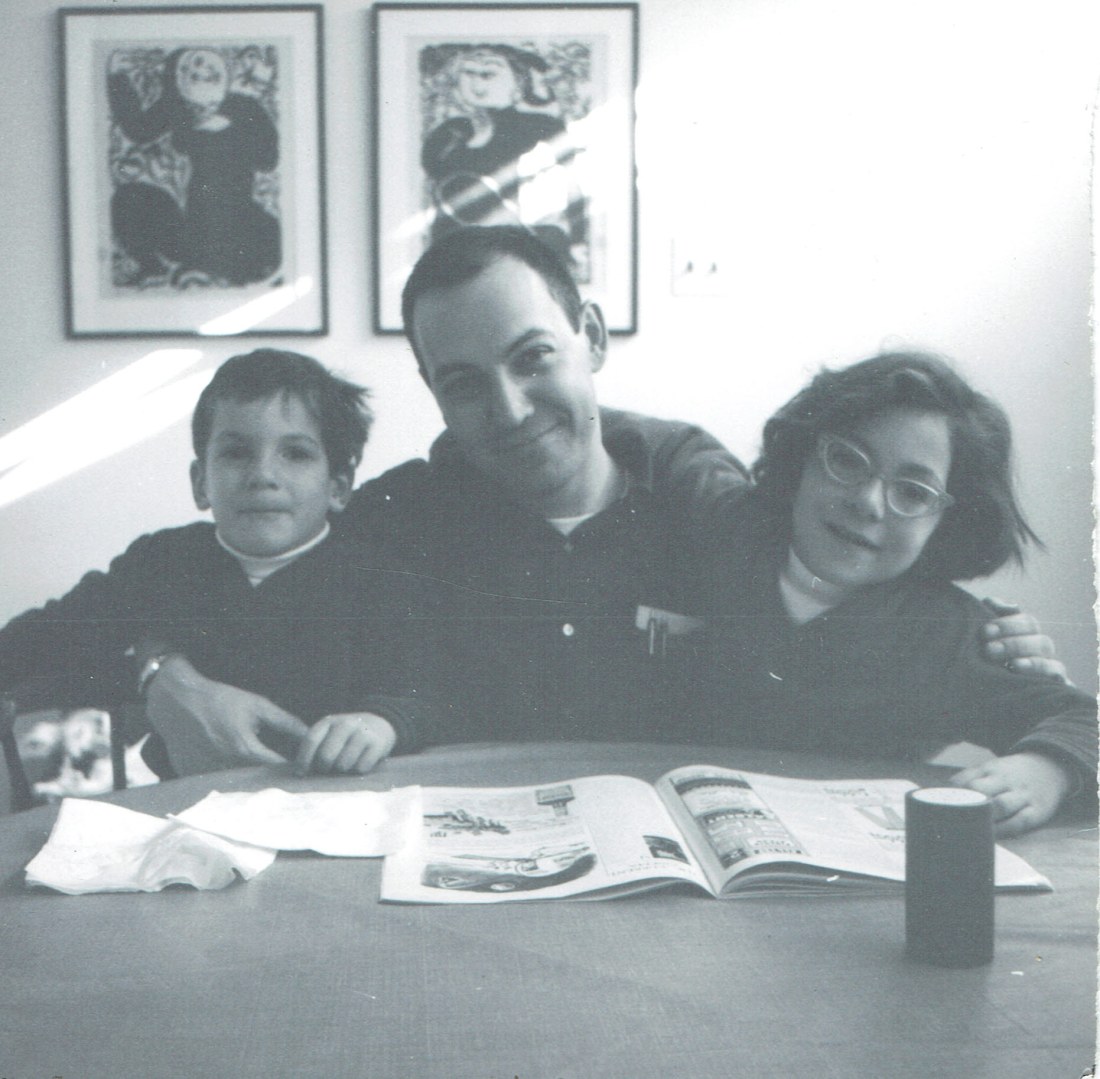

We met Harry almost 30 years ago. My husband was assessing a problem at Harry’s mother’s house and they met there. He did some work for him, and they hit it off. Soon after, I met Harry’s wife. She was a warm and welcoming person and soon we became a foursome.

While pregnant with our daughter, we invited them on a boat trip. In the warm, shallow water on a late summer Sunday afternoon, we floated on rafts and tubes and shared our nervousness about becoming new parents with two people who had recently become empty nesters. Their easy manner and gentle encouragement erased our fears. The following winter after our daughter was born, his wife cooed over the baby and got great enjoyment over holding her and trying to get her to smile.

About a year later, we received the news that his wife had arisen in the middle of the night, gone out in the backyard in her nightgown, and shot herself. Harry, who was partially deaf, had not heard anything. Their grown son located her early the next day when he stopped in and found Harry still sleeping and his mother nowhere to be found inside. Harry had been a firearms instructor; there were guns in the house and she had made use of one.

Immediately, the irrational thoughts plagued us: How could we have not detected that something was wrong? She was eternally cheery in our presence and always ready for a night out or a visit with the baby. We even had tickets to a show together the following week–why didn’t she look forward to that as a remedy for whatever was plaguing her thoughts? We were naive.

Then came the clues. She was a human resources officer whose large facility was going through a reduction in force. Her job was to sit with each employee, explain that they were being laid off, and provide them with resources. She never mentioned this to us; it was something I found out by talking with her friends later. Worse still, Harry told us that her father had also committed suicide. At a family gathering, he had risen from his chair, excused himself, went down to the basement, and shot himself.

At the cemetery, his daughter clutched her mother’s sweater in her hands and wailed at her grave, shouting at times, “Why? Why? Whyyyy?” I’ve never been able to shake that scene from my mind.

The years went on. His son became a missionary worker and was out of the country most of the time. When he finally returned to the States, he settled in North Carolina and started a massage therapy business, rarely visiting his family. Harry was a regular visitor to our house, though, where he and my husband would talk after dinner about almost anything but his family.

Then, Harry lost one of his legs. An unrepentant smoker, the blood clot that led to the amputation was the thing that finally convinced him to stop. He was only in his early 70s at the time and insisted on staying in his home. At some point, his son bought him a King Charles Spaniel to keep him company and Harry rented out the basement. He spent all day sitting in one spot in the living room very close to a large TV that was tuned mainly to nature shows.

We moved over an hour away. When we visited, the clutter of his surroundings and the stench of the dog were overwhelming. He would indicate that the doorbell was still broken and chuckle under his breath. During one visit, he told us the telephone handset had been in need of a new battery for a while, so we went out and found a replacement.

The next crisis was a series of phone calls where Harry confided that he believed his son was stealing from him, forging his father’s name on stolen checks. He intimated that his son was in trouble, but provided no details. Where his son was at this time is unclear, but there was probably a lot Harry did not know or did not want us to know. Several times we urged him to call the police or at least get to the bank and open an investigation. He talked about doing this, but we are not sure that he ever followed through.

His son finally moved home around 2015, remorseful and unemployed. He asked forgiveness, and slept on the floor at the foot of Harry’s bed for months. Soon after, we received another tragic phone call: his son had arisen in the middle of the night, gone downstairs to the utility room, and hung himself. He was 48.

The funeral was packed with his son’s friends and their families. Harry sat in the front of the chapel in his wheelchair, looking straight ahead. I looked for his daughter and her family. They were sitting on the other side of the chapel. Harry’s son-in-law was dressed inappropriately for a funeral, in bright casual clothing, and he was loud and obnoxious. As the service started, the family made no move to sit closer to Harry. I thought, “What is going on here?”

The service was filled with fond remembrances of his son, eulogies given by a childhood minister and high school buddies. Many recalled how Harry’s son had been very giving of himself and his time and helped people with their problems. After the service, the chapel emptied out. We sat and watched as people exited until almost everyone was out in the parking lot. Not one person went to Harry to extend their condolences. We quietly approached him. He was dry-eyed and calm. He let us hug him and say a few words, and then we left.

It was only later that we reflected on the scene and came to the realization that probably no one knew how bad things had become for his son, or they knew and were in denial. It was clear that Harry’s daughter and her husband were angry at Harry (thus the obnoxious clothing and behavior) and blamed him, and that’s why they refused to sit with him or offer him any comfort. Somehow, it seemed that everyone in the chapel except us was in on this judgement of Harry.

We continued to check up on Harry every few months whenever business brought us to his town. The house decayed. The renter moved out. He seemed to be completely alone, but he told us Meals on Wheels brought him hot food. When we asked about his daughter, he was vague.

And then it was winter of this year. We pulled up to the house and tried the doorbell. Of course, it still wasn’t working so we knocked on the door. There was no answer, no dog barking, no loud television. The car sat in the driveway, but it was obvious that it had not been driven in a while. We decided to see if any neighbors were home and knew what was going on.

After a few tries, a woman three doors down appeared. We asked if she knew Harry. “Oh my,” she said, “you haven’t heard.” Harry had died just a few days before, and the funeral was in two days. He had been taken from his home by his daughter and placed in a nursing home closer to her about six months earlier. She shook her head, “There were so many troubles in that family. Years ago, I would go outside in the evening. I’d see Harry in his car, drinking. I told him he needed help.” It turns out that this kind neighbor had been watching out for him over the years and checking up on him after he lost mobility, but we had no idea.

At his funeral, his remaining family sat quietly. There were no personal stories or fond recollections from anyone. The minister delivered a harsh eulogy about how Harry was not an easy person to live with, how he had caused pain to his loved ones, and then made reference to Bible passages that were meant to comfort us somehow.

I was shocked that a minister would refer to the deceased with such condemnation. Was the minister really talking about our friend? Were we in the wrong chapel, perhaps? We knew Harry as a troubled man; the scepter of death hung over him every day, but we could not imagine him being a purposefully cruel person as a result, ever.

Something had nudged at us to check up on Harry on that cold February day, otherwise we would never have found out that he had left us. I have a feeling that we and his neighbor were his only real friends, but that he subconsciously shared with us only what he thought we needed to know. He was more private than we ever realized, not because he was manipulative, but because he just couldn’t cope with his losses. He didn’t get the doorbell fixed because he didn’t know how to deal with whatever walked in the door with a visitor. You think you know a person, until you don’t.